I want to tell young girls and women: Always follow your dreams, no matter what. Just go for it because in the end, it’s worth it.

Série Femmes, filles et sciences

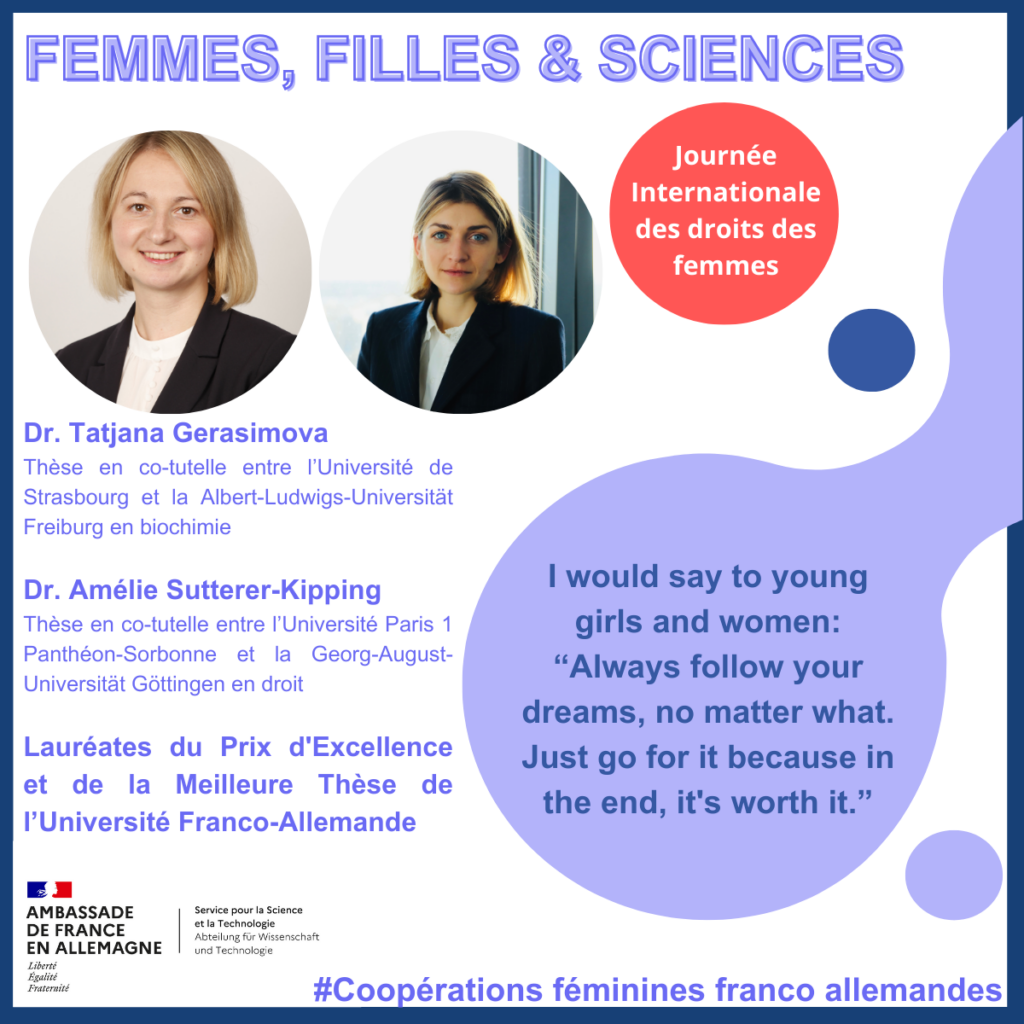

Entretien avec Tatjana Gerasimova et Amélie Sutterer-Kipping, lauréates du Prix de la Meilleure Thèse de l’Université Franco-Allemande 2024.

Le Service pour la science et la technologie de l’Ambassade de France en Allemagne met en lumière aux mois de février et mars 2025, des femmes scientifiques, en particulier des coopérations franco-allemandes scientifiques féminines.

A l’occasion de la Journée Inernationale des droits des femmes, le 08 mars, deux chercheuses, Dr. Tatjana Gerasimova, qui a réalisé une thèse en co-tutelle entre l’Université de Strasbourg et la Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg en biochimie, et Dr. Amélie Sutterer-Kipping, qui a réalisé une thèse en co-tutelle entre l’Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne et la Georg-August-Universität Göttingen en droit, répondent à nos questions.

Tatjana Gerasimova a été récompensée pour sa thèse : « Décryptage des mécanismes des complexes de la chaîne respiratoire par marquage IR et approches exaltées de surface ». Amélie Sutterer-Kipping a été récompensée pour sa thèse « Le portage salarial – un modèle pour les travailleurs indépendants (solos) en Allemagne ? »

Elles sont lauréates du Prix de la Meilleure Thèse de l’Université Franco-Allemande 2024, un prix qui récompense les travaux de recherche d’excellent niveau de jeunes docteurs et docteures ayant bénéficié du soutien de l’UFA. Toutes les informations sont à retrouver ici : https://www.dfh-ufa.org/fr/vous-etes/entreprises/prix-de-la-meilleure-these?noredirect=fr_FR

Can you introduce yourself, your studies and your research?

Tatjana Gerasimova: My name is Tatjana Gerasimova, and I am originally from Latvia. I moved to Germany in 2015 to pursue a master’s degree in chemistry. After that, I completed a PhD in biochemistry through a binational program between Germany and France. My research focused on investigating an enzyme from the respiratory chain, whose mechanism of action remains a topic of debate. While various theories exist, a definitive answer is still missing. To address this mystery, a multidisciplinary approach was applied. My PhD work was conducted between the University of Freiburg and the University of Strasbourg. In Freiburg, I used biochemical methods to obtain protein samples, which were later analyzed using spectroscopy in Strasbourg. I was honored to work on this pioneering project, as I was the first to apply these methods to such a large protein. The findings could contribute to clarifying the enzyme’s mechanism. Additionally, I found it fascinating to work in two countries simultaneously, as it provided valuable insights and opened up many opportunities.

Amélie Sutterer-Kipping: I am Amélie Sutterer-Kipping. I am half French, half German, and I grew up in Germany. I studied law in Munich and then I did my PhD in Göttingen. My PhD Director had already supervised a binational PhD and proposed this as an opportunity to me. My German PhD Director then supported me throughout the entire process and put me in touch with my French ‘directeur de thèse’ in Paris. This is how I had the opportunity to write a part of my thesis in Paris 1 Panthéon Sorbonne for three years. After finishing my thesis, I was able to find a job in Germany, at the Hugo Sinzheimer Institute in Frankfurt, an institute for labour and social security law. I started in 2022, and now I am the head of our department for labour and social security law. At the moment I am mainly working on the implementation of the European Platform Work Directive. In addition, working time, the fair distribution of care work and pay transparency are a focus of my research and lecturing activities. I am also a lecturer at the European Academy for Work at the University of Frankfurt for European Labor Law.

What motivated you to start studying in your field?

Amélie Sutterer-Kipping: I started studying law and specialized in labour law for my thesis because, unlike other areas of law, it not only deals with human beings, it is about human beings and their lives. It is such an accessible and tangible area of law. During my time as a research assistant at the University of Göttingen, I worked with my PhD Director on a research project investigating the social risks of old age, illness and unemployment associated with part-time and fixed-term contracts or self-employment, particularly in relation to how such employment relationships later affect pensions. That’s where I got the idea for the topic of my thesis. I wanted to find solutions to the challenges of precarious solo self-employment. I am now continuing this work, with a particular focus on the working conditions of platform workers.

Tatjana Gerasimova: I developed a strong interest in life sciences during high school, which motivated me to study chemistry. I am also deeply interested in pharmaceutical research because it allows me to make a meaningful impact and improve people’s lives. During my PhD, I focused on uncovering the mechanism of a specific protein, whose mutations can lead to severe neurodegenerative diseases such as Leigh syndrome, Alzheimer’s. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for developing effective treatments for patients suffering from these conditions. Contributing to this field and making a difference has always been important to me. This week, I started a new position as a Senior Scientist in Quality Control at Lonza in Visp, Switzerland. I am happy that my work can contribute to improving people’s lives.

Is gender a subject in your research?

Amélie Sutterer-Kipping: Gender is definitely a big issue in my work at the Institute. We do research on gender-equitable access to the labour market and gender-equitable working conditions. In Germany, women still do most of the care work and reduce their working hours to do so. Recently, we had new statistics showing that, for example, women spend nine hours a week more than men on care work, and even more if they work remotely. In the medium to long term, this increases the gender pay gap and ultimately the gender pension gap. In 2019, women in Germany received 49 % less pension income than men. Part-time work is not generally bad and can help reconcile work and family life, but the framework conditions must be right. The decision must be voluntary and the reduction in working hours must ensure an independent livelihood throughout of a person’s life. We contribute to this topic with our conferences and studies, for example on the implementation of the European Pay Transparency Directive.

Tatjana Gerasimova: I wouldn’t say that gender was a focus of my PhD, as I was working in the field of biochemistry and conducting fundamental research. However, I did notice that many of my colleagues in science were women, which I see as a very positive sign.

How do you experience the impact of gender in your daily life?

Amélie Sutterer-Kipping: During my studies, when I worked at the university, I didn’t have any bad experiences myself. On the contrary, there were more women than men at our chair. But I think later on, if you want to stay in research and become a professor, for example, it’s quite difficult because you often only have a fixed-term contract. In Germany, if you study law and then do a PhD, you are about 30 when you finish. Although, fixed-term contracts give employers a certain degree of flexibility, they create a great deal of uncertainty for employees. This affects not only their professional and financial situation, but also their family planning, for both men and women. At the same time, there are also differences, as many of the protections we have put in place to protect women become ineffective on fixed term contracts: for example, maternity protection. As long as the employment relationship continues, maternity protection for fix-term positions is no different from maternity protection for permanent positions. But when your employment contract ends, your maternity protection also ends.

Tatjana Gerasimova: I agree with Amélie about the challenges of fixed-term contracts. I also believe that if a woman chooses to stay in science and competes with a male researcher, building a career while planning a family can be quite challenging. However, during my PhD studies, I didn’t personally feel that gender had a significant impact on my experience. For me, the real challenge was finding a job after completing my PhD. I think that at this stage, many employers may assume that women are planning to start a family, which can affect hiring decisions. While things are gradually changing, men can still have certain advantages in the job market. I truly hope that, in the future, the job market will offer equal opportunities regardless of gender.

Did you feel supported by your colleagues?

Amélie Sutterer-Kipping: I was supported by all the students and colleagues at the Institute de Recherche juridique de la Sorbonne (IRJS). Even though I didn’t work there, I was just a PhD guest student, I had my own desk and was made to feel welcome immediately. They always took the time to introduce me to student life in Paris. I felt a sense of belonging right from the beginning. I am very grateful to them.

Tatjana Gerasimova: I also experienced this kind of support. When I arrived in Strasbourg from Germany, all my colleagues at the time—both PhD students and postdocs—were women. We even created a chat group called « Girls Lab, » which was a great source of support. Everyone was very welcoming, and I felt truly included. In my German lab in Freiburg, the gender distribution was roughly 50/50 between female and male researchers, but it was also a fantastic team. At the University of Freiburg, there is a special mentoring program called Kite Mentoring, designed exclusively to support women in science. It serves as a network for projects, exchange, training, and long-term support, promoting career development.

Amélie Sutterer-Kipping: Mentoring programmes are a good thing and, above all, a lot of fun. I’ve recently become a mentor myself, in a programme run by the University of Passau: a student from Passau comes to Munich every two or three months and we talk about her studies and her career.

Did you notice differences between France and Germany?

Amélie Sutterer-Kipping: My impression in Paris was that childcare is better organized and, compared to Germany, fathers in France have long had the right to paternity leave immediately after the birth of a child. We could really use that as an example.

Tatjana Gerasimova: I would say I didn’t notice any significant differences. I know that in Germany, maternity leave lasts about one year, whereas in France, it is only four months.

What advice would you give to girls and young women that have an interest for science?

Amélie Sutterer-Kipping: I would say to girls and young women: go for it, as it is an enriching experience. You have the privilege of researching a very specific question, which otherwise is not possible in everyday life. In the end, you will be the expert in this field of research. At the same time, this period is also characterized by loneliness and self-doubt, which makes it all the more important to support and encourage each other. I would strongly encourage young women, but actually every young researcher, to take part in mentoring programmes and colloquia, and to find out about scholarships well in advance.

Tatjana Gerasimova: I agree with Amélie. I would say to the young girls, always follow your dreams, no matter what. It doesn’t matter which gender, just go for it because in the end, it’s worth it.

Entretien réalisé en anglais le 05 mars 2025 par Julie LE GALL et Noela MULLER,

du Service pour la Science et la Technologie de l’Ambassade de France en Allemagne.